Special Dispatch: Normal Computing’s Thermodynamic Chip

Noise, heat, and the next frontier in AI hardware

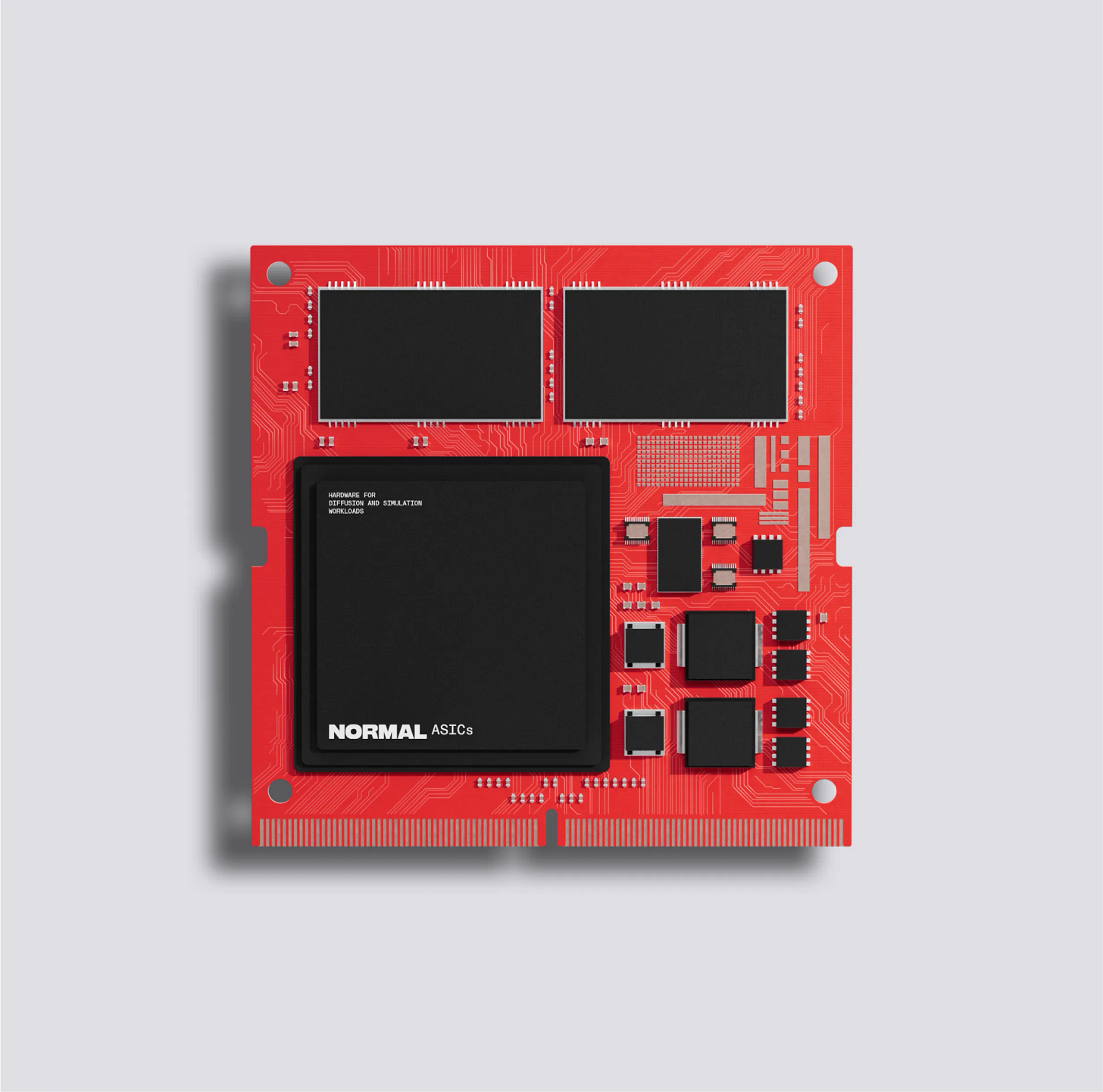

Normal Computing’s thermodynamic processor, which looks to reduce AI energy usage by a factor of 1000. Image credit: Normal Computing

New York-based Normal Computing just made a bold claim: they’ve built the world’s first thermodynamic processor.

Not a GPU, but a new kind of analog computing core that replaces Boolean logic, using heat and noise as signals, not problems to be fixed. This sounds a little out there, but if the physics holds and the architecture scales, it could represent the most meaningful shift in computation since the dawn of the microprocessor in 1971.

We can pump the brakes a little- this has just been designed and “taped out”, meaning the design has been finalized and sent to the fab. There’s a long road of testing ahead before commercialization.

What’s the Big Deal?

This isn’t about marginal efficiency gains. Normal Computing is claiming three orders of magnitude improvement in energy use for probabilistic workloads, especially in machine learning and AI inference.

Their chip is analog, probabilistic, and grounded in the core laws of thermodynamics. Basically, instead of forcing bits into binary states using precise voltages and timing, it utilizes the thermal noise (heat energy) that is created as a probability distribution, which it uses in computation. The result is increased speed and decreased energy consumption for certain specific (but critical) cases.

If we look at a very rough analogy, consider the use of statistical modeling in demand forecasting to determine production or inventory. Historically, planners may have settled on an average or small range, but ignored the broader distribution. Modern best practice is to not only consider the distribution, but to actively track error- which was previously considered noise.

Just as this noise can be used to determine safety stock levels (improving the quality of future forecasting), the thermodynamic processor aims to use thermal noise to model probability distributions, which are in turn used in computation, particularly for AI.

Background

Before diving into what’s new, it’s worth briefly revisiting the foundational concepts:

Moore’s Law: An empirical observation first noticed by Gordon Moore, stating that the number of transistors on an IC doubles about every 18-24 months. This has essentially held true since the late 1960s, fueling most of the growth in computing power, but it’s coming up against hard economic and physical limits.

Landauer Limit: The minimum amount of energy required to erase one bit of information; a thermodynamic floor for digital logic.

Thermal noise: In traditional computing, it’s treated as interference. Here, it’s the raw material of computation.

Boltzmann distribution (below): A statistical model that describes the likelihood of particles occupying various energy states. Normal Computing’s chip reportedly uses this principle in hardware form.

All of this ties into the broader slowdown of Moore’s Law and the growing physical and economic limits of transistor-based scaling. If computation can’t keep getting cheaper and faster the old way, new approaches are on the table.

How does this work?

The Boltzmann distribution is essential for understanding the key principle here. In reality, there’s a big difference between useful noise or randomness and “wrong” randomness. In our analogy, think of this as the difference between capturing true raw demand data and skewed, biased, or data that’s otherwise affected in some way.

In the processor, thermal noise is governed by physical factors- voltage, current, materials, and circuit parameters. This random noise may be different from the probability distribution that is needed for the computation. Mapping between these is the biggest technical challenge.

The Boltzmann distribution is a statistical law defining how physical systems engage with and explore energy states- essentially the distribution of probabilities of these different energy states that arises. If the computational problem follows the same structure that arises in the system, there are no issues. However, if the two are even slightly different, there will be bias in the samples. Therefore, this new class of processor will likely require some form of calibration to account for this.

Normal Computing controls this a couple of different ways: controllable parameters (such as temperature / noise amplitude), and hybrid digital-analog control loops (digital systems watching the analog core and making adjustments).

Implications for Electronics

Who uses this?

The first applications will likely be in edge AI and energy-constrained environments- this would include autonomous drones, mobile robotics, IoT inference, and probabilistic simulations.

What changes?

If this architecture delivers even half of what’s promised, it would shift multiple parts of the semiconductor and electronics stack:

Chip design: New analog-core architectures, distinct from existing digital logic.

Packaging: Thermodynamic chips may have distinct thermal management, shielding, or calibration needs.

Fabrication: Foundries accustomed to digital logic may need to adapt to analog-optimized processes.

Sourcing: Analog components have different suppliers, tolerances, and visibility challenges than digital logic.

Supply chain implications

Are sourcing teams prepared to track the availability and compliance of analog thermodynamic cores?

Are fabs equipped to handle the yield variability of these components?

Could demand for conventional GPUs decline in narrow workloads?

Practical Takeaways

Track Normal Computing’s early results closely: If tape-out and test data support their claims, the ripple effects could be rapid, especially in AI-adjacent markets.

Begin mapping analog sourcing capabilities: Identify vendors, materials, and packaging partners who support analog thermodynamic workflows.

Flag legacy assumptions: Many EMS workflows, sourcing risk models, and supplier networks assume deterministic digital logic. Those assumptions may not hold.

The impact of this is likely going to be targeted and specific to a few key use cases, let alone industries, at first, but it’s hard to overstate just how enormous a change this could be for computing. The design has been solidified and Normal Computing has moved from 0 to 1, and while there may be scaling challenges ahead, this first step is the largest one.